Traditional endocrinology

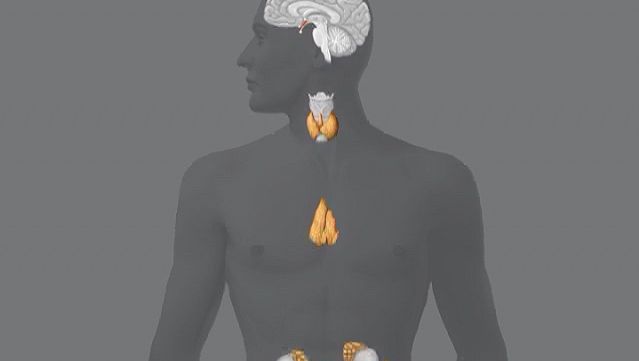

The body of knowledge of the endocrine system is continually expanding, driven in large part by research that seeks to understand basic cell functions and basic mechanisms of human endocrine diseases and disorders. The traditional core of an endocrine system consists of an endocrine gland, the hormone it secretes, a responding tissue containing a specific receptor to which the hormone binds, and an action that results after the hormone binds to its receptor, termed the postreceptor response.

Each endocrine gland consists of a group of specialized cells that have a common origin in the developing embryo. Some endocrine glands, such as the thyroid gland and the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas, are derived from cells that arise in the embryonic digestive system. Other endocrine glands, such as the parathyroid glands and the adrenal medulla, are derived from cells that arise in the embryonic nervous system. Certain glands, including the ovary, testis, and adrenal cortex, arise from a region of the embryo known as the urogenital ridge. There are also several glands that are derived from cells that originate in multiple regions of the embryo. For example, the pituitary gland is composed of cells from the nervous system and the digestive tract.

Each endocrine gland also has a rich supply of blood vessels. This is important not only because nutrients are delivered to the gland by the blood vessels but also because the gland cells that line these vessels are able to detect serum levels of specific hormones or other substances that directly effect the synthesis and secretion of the hormone the gland produces. Hormone secretion is sometimes very complex, because many endocrine glands secrete more than one hormone. In addition, some organs function both as exocrine glands and as endocrine glands. The best-known example of such an organ is the pancreas.

In addition to traditional endocrine cells, specially modified nerve cells within the nervous system secrete important hormones into the blood. These special nerve cells are called neurosecretory cells, and their secretions are termed neurohormones to distinguish them from the hormones produced by traditional endocrine cells. Neurohormones are stored in the terminals of neurosecretory cells and are released into the bloodstream upon stimulation of the cells.

Most hormones are one of two types: protein hormones (including peptides and modified amino acids) or steroid hormones. The majority of hormones are protein hormones. They are highly soluble in water and can be transported readily through the blood. When initially synthesized within the cell, protein hormones are contained within large biologically inactive molecules called prohormones. An enzyme splits the inactive portion from the active portion of the prohormone, thereby forming the active hormone that is then released from the cell into the blood. There are fewer steroid hormones than protein hormones, and all steroid hormones are synthesized from the precursor molecule cholesterol. These hormones (and a few of the protein hormones) circulate in the blood both as hormone that is free and as hormone that is bound to specific proteins. It is the free unbound hormone that has access to tissues to exert hormonal activity.

Hormones act on their target tissues by binding to and activating specific molecules called receptors. Receptors are found on the surface of target cells in the case of protein and peptide hormones, or they are found within the cytoplasm or nuclei of target cells in the case of steroid hormones and thyroid hormones. Each receptor has a strong, highly specific affinity (attraction) for a particular hormone. A hormone can have an effect only on those tissues that contain receptors specific for that hormone. Often, one segment of the hormone molecule has a strong chemical affinity for the receptor while another segment is responsible for initiating the hormone’s specific action. Thus, hormonal actions are not general throughout the body but rather are aimed at specific target tissues.

A hormone-receptor complex activates a chain of specific chemical responses within the cells of the target tissue to complete hormonal action. This action may be the result of the activation of enzymes within the target cell, interaction of the hormone-receptor complex with the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in the nucleus of the cell (and consequent stimulation of protein synthesis), or a combination of both. It may even result in the secretion of another hormone.

Function of the endocrine system

The nature of endocrine regulation

Endocrine gland secretion is not a haphazard process; it is subject to precise, intricate control so that its effects may be integrated with those of the nervous system and the immune system. The simplest level of control over endocrine gland secretion resides at the endocrine gland itself. The signal for an endocrine gland to secrete more or less of its hormone is related to the concentration of some substance, either a hormone that influences the function of the gland (a tropic hormone), a biochemical product (e.g., glucose), or a biologically important element (e.g., calcium or potassium). Because each endocrine gland has a rich supply of blood, each gland is able to detect small changes in the concentrations of its regulating substances.

Some endocrine glands are controlled by a simple negative feedback mechanism. For example, negative feedback signaling mechanisms in the parathyroid glands (located in the neck) rely on the binding activity of calcium-sensitive receptors that are located on the surface of parathyroid cells. Decreased serum calcium concentrations result in decreased calcium receptor binding activity that stimulates the secretion of parathormone from the parathyroid glands. The increased serum concentration of parathormone stimulates bone resorption (breakdown) to release calcium into the blood and reabsorption of calcium in the kidney to retain calcium in the blood, thereby restoring serum calcium concentrations to normal levels. In contrast, increased serum calcium concentrations result in increased calcium receptor-binding activity and inhibition of parathormone secretion by the parathyroid glands. This allows serum calcium concentrations to decrease to normal levels. Therefore, in people with normal parathyroid glands, serum calcium concentrations are maintained within a very narrow range even in the presence of large changes in calcium intake or excessive losses of calcium from the body.

Control of the hormonal secretions of other endocrine glands is more complex, because the glands themselves are target organs of a regulatory system called the hypothalamic-pituitary-target gland axis. The major mechanisms in this regulatory system consist of complex interconnecting negative feedback loops that involve the hypothalamus (a structure located at the base of the brain and above the pituitary gland), the anterior pituitary gland, and the target gland. The hypothalamus produces specific neurohormones that stimulate the pituitary gland to secrete specific pituitary hormones that affect any of a number of target organs, including the adrenal cortex, the gonads (testes and ovaries), and the thyroid gland. Therefore, the hypothalamic-pituitary-target gland axis allows for both neural and hormonal input into hormone production by the target gland.

When stimulated by the appropriate pituitary hormone, the target gland secretes its hormone (target gland hormone) that then combines with receptors located on its target tissues. These receptors include receptors located on the pituitary cells that make the particular hormone that governs the target gland. Should the amount of target gland hormone in the blood increase, the hormone’s actions on its target organs increases. In the pituitary gland, the target gland hormone acts to decrease the secretion of the appropriate pituitary hormone, which results in less stimulation of the target gland and a decrease in the production of hormone by the target gland. Conversely, if hormone production by a target gland should decrease, the decrease in serum concentrations of the target gland hormone leads to an increase in secretion of the pituitary hormone in an attempt to restore target gland hormone production to normal. The effect of the target gland hormone on its target tissues is quantitative; that is, within limits, the greater (or lesser) the amount of target gland hormone bound to receptors in the target tissues, the greater (or lesser) the response of the target tissues.

In the hypothalamic-pituitary-target gland axis, a second negative feedback loop is superimposed on the first negative feedback loop. In this second loop, the target gland hormone binds to nerve cells in the hypothalamus, thereby inhibiting the secretion of specific hypothalamic-releasing hormones (neurohormones) that stimulate the secretion of pituitary hormones (an important element in the first negative feedback loop). The hypothalamic neurohormones are released within a set of veins that connects the hypothalamus to the pituitary gland (the hypophyseal-portal circulation), and therefore the neurohormones reach the pituitary gland in high concentrations. Target gland hormones effect the secretion of hypothalamic hormones in the same way that they effect the secretion of pituitary hormones, thereby reinforcing their effect on the production of the pituitary hormone.

The importance of the second negative feedback loop lies in the fact that the nerve cells of the hypothalamus receive impulses from other regions of the brain, including the cerebral cortex (the centre for higher mental functions, movement, perceptions, emotion, etc.), thus permitting the endocrine system to respond to physical and emotional stresses. This response mechanism involves the interruption of the primary feedback loop to allow the serum concentrations of hormones to be increased or decreased in response to environmental stresses that activate the nervous system. The end result of the two negative feedback loops is that, under ordinary circumstances, hormone production by target glands and the serum concentrations of target gland hormone are maintained within very narrow limits but that, under extraordinary circumstances, this tight control can be overridden by stimuli originating outside of the endocrine system.

There are important supplemental mechanisms that control endocrine function. When more than one cell type is found within a single endocrine gland, the hormones secreted by one cell type may exert a direct modulating effect upon the secretions of the other cell types. This form of control is known as paracrine control. Similarly, the secretions of one endocrine cell may alter the activity of the same cell, an activity known as autocrine control. Thus, endocrine cell activity may be modulated directly from within the endocrine gland itself, without the need for hormones to enter the bloodstream.

If the requirement that a hormone act at a site remote from the endocrine cells in which the hormone is produced is excluded from the defining characteristics of hormones, additional classes of biologically active materials can be considered as hormones. Neurotransmitters, a group of chemical compounds of variable composition, are secreted at all synapses (junctions between nerve cells over which nervous impulses must travel). They facilitate or inhibit the transmission of neural impulses and have given rise to the science of neuroendocrinology (the branch of medicine that studies the interaction of the nervous system and the endocrine system). A second group of biologically active substances is called prostaglandins. Prostaglandins are a complex group of fatty acid derivatives that are produced and secreted by many tissues. Prostaglandins mediate important biological effects in almost every organ system of the body.

Another group of substances, called growth factors, possess hormonelike activity. Growth factors are substances that stimulate the growth of specific tissues. They are distinct from pituitary growth hormone in that they were identified only after it was noted that target cells grown outside the organism in tissue culture could be stimulated to grow and reproduce by extracts of serum or tissue chemically distinct from growth hormone.

Still another area of hormonal activity that has come under intensive investigation is the effect of endocrine hormones on behaviour. While simple direct hormonal effects on human behaviour are difficult to document because of the complexities of human motivation, there are many convincing demonstrations of hormone-mediated behaviour in other life-forms. A special case is that of the pheromone, a substance generated by an organism that influences, by its odour, the behaviour of another organism of the same species. An often-quoted example is the musky scent of the females of many species, which provokes sexual excitation in the male. Such mechanisms have adaptive value for species survival.