Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is a part of the brain that has a vital role in controlling many bodily functions including the release of hormones from the pituitary gland.

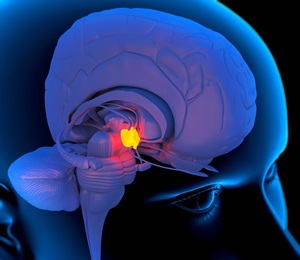

Where is my hypothalamus?

Computer artwork of a person’s head showing the left side of the brain with the hypothalamus highlighted.

The hypothalamus is located on the undersurface of the brain. It lies just below the thalamus and above the pituitary gland, to which it is attached by a stalk. It is an extremely complex part of the brain containing many regions with highly specialised functions. In humans, the hypothalamus is approximately the size of a pea and accounts for less than 1% of the weight of the brain.

What does my hypothalamus do?

One of the major functions of the hypothalamus is to maintain homeostasis, i.e. to keep the human body in a stable, constant condition.

The hypothalamus responds to a variety of signals from the internal and external environment including body temperature, hunger, feelings of being full up after eating, blood pressure and levels of hormones in the circulation. It also responds to stress and controls our daily bodily rhythms such as the night-time secretion of melatonin from the pineal gland, diurnal changes in cortisol (the stress hormone) and body temperature over a 24-hour period. The hypothalamus collects and combines all this information and puts changes in place to correct any imbalances.

What hormones does my hypothalamus produce?

There are two sets of nerve cells in the hypothalamus that produce hormones. One set of cells sends the hormones they produce down through the pituitary stalk to the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland where these hormones are released directly into the bloodstream. These hormones are anti-diuretic hormone (also known as Vasopressin) and oxytocin. Anti-diuretic hormone regulates the amount of fluid in the body and causes water reabsorption at the kidneys thus preventing dehydration. Oxytocin stimulates contraction of the uterus in childbirth and is important in breastfeeding.

The other set of nerve cells produces stimulating and inhibiting hormones that reach the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland via a network of blood vessels that run down through the pituitary stalk. These regulate the production of hormones that control the gonads, thyroid gland and adrenal cortex, as well as the production of growth hormone, which regulates growth, and prolactin, which is essential for milk production. The hormones produced in the hypothalamus are corticotrophin-releasing hormone, dopamine, growth hormone-releasing hormone, somatostatin, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone and thyrotrophin-releasing hormone.

What could go wrong with my hypothalamus?

Hypothalamic function can be affected by head trauma, brain tumours, infection, inflammatory diseases, surgery, radiation and significant weight loss. It can lead to disorders of energy balance and thermoregulation, disorganised body rhythms, (insomnia) and symptoms of pituitary deficiency due to loss of hypothalamic control. Pituitary deficiency (hypopituitarism) ultimately causes a deficiency of hormones produced by the gonads, adrenal cortex and thyroid gland, as well as loss of growth hormone. Prolactin however may increase due to loss of negative feedback from dopamine.

Lack of anti-diuretic hormone production by the hypothalamus causes diabetes insipidus. In this condition the kidneys are unable to reabsorb water and produce more concentrated urine. As a result too much water is passed through the body as dilute urine. Patients thus have excessive thirst as their bodies try to make up for the increased loss of water.