Endocrine System

The endocrine system is a collection of ductless glands that produce hormones and secrete them into the circulatory system. Endocrine glands work without ducts for carrying secretions towards target organs. Instead, hormones can act as chemical messengers for a large number of cells and tissues simultaneously.

Overview

The endocrine system consists of many glands, which work by secreting hormones into the bloodstream to be carried to a target cell. Endocrine system hormones work even if the target cells are distant from the endocrine glands. Through these actions, the endocrine system regulates nearly every metabolic activity of the body to produce an integrated response. The endocrine system can release hormones to induce the stress response, regulate the heartbeat or blood pressure, and generally directs how your cells grow and develop.

Endocrine glands are usually heavily vascularized, containing a dense network of blood vessels. Cells within these organs produce and contain hormones in intracellular granules or vesicles that fuse with the plasma membrane in response to the appropriate signal. This action releases the hormones into the extracellular space, or into the bloodstream. The endocrine system can be activated by many different inputs, allowing for responses to many different internal and external stimuli.

Endocrine System Function

The endocrine system, along with the nervous system, integrates the signals from different parts of the body and the environment. In addition, the endocrine system produces effector molecules in the form of hormones that can elicit an appropriate response from the body in order to maintain homeostasis. The nervous system produces immediate effects. The endocrine system is designed to be relatively slow to initiate, but it has a prolonged effect.

As an example, the long-term secretion of growth hormone in the body influences the development of bones and muscles to increase height and also induces the growth of every internal organ. This happens over the course of many years. Hormones like cortisol, produced during times of stress, can change appetite, and metabolic pathways in skeletal and smooth muscle for hours or weeks.

The endocrine system is involved in every process of the human body. Starting from the motility of the digestive system, to the absorption and metabolism of glucose and other minerals, hormones can affect a variety of organs in different ways. Some hormones affect the retention of calcium in bones or their usage to power muscle contraction. In addition, they are involved in the development and maturation of the adaptive immune system, and the reproductive system. Crucially, they can affect overall growth and metabolism, changing the way every cell assimilates and utilizes key nutrients.

Endocrine System Parts

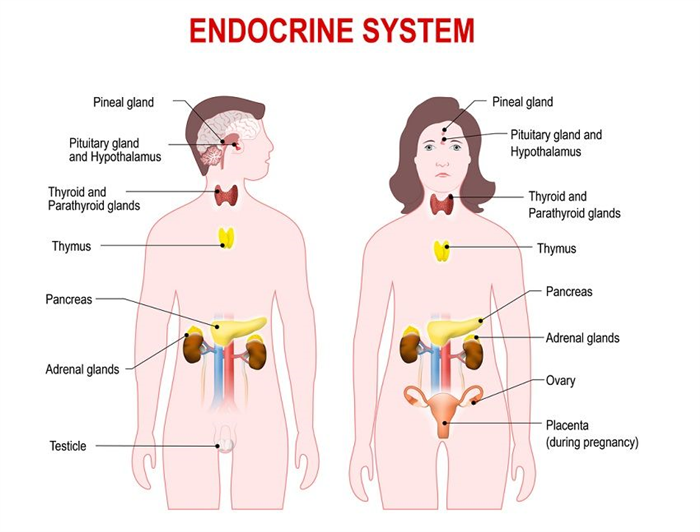

The endocrine system consists of a number of organs – some of which have hormone production as their primary function, while others play important roles in other organ systems as well. These include the pituitary and pineal glands in the brain, the thyroid and parathyroid glands in the neck, the thymus in the thoracic region, the adrenals and pancreas in the abdominal region and the gonads in the reproductive system.

Endocrine System in the Brain

Starting from the brain, the hypothalamus, pituitary and pineal glands are involved in the regulation of other endocrine organs and in the regulation of circadian rhythms, changing the metabolic state of the body. The pineal gland is located near the center of the brain, in a region called the epithalamus. The pituitary gland is seen very near the hypothalamus and has some direct interactions and feedback loops with the organ for the production of hormones.

Together, the hypothalamus and pituitary can regulate a number of endocrine organs, particularly the gonads, and the adrenals. In fact, the hypothalamus can be considered as the nodal point that integrates two major pathways for regulation – the nervous and endocrine systems. It is made of a collection of neurons that collect information from the body through the nervous system and integrate it into a response through the endocrine system, especially the anterior and posterior parts of the pituitary gland.

Endocrine System within the Neck

The neck contains the thyroid and parathyroid glands. The thyroid gland consists of two symmetric lobes connected by a narrow strip of tissue called the isthmus glandularis, forming a butterfly-like structure. Each lobe is about 5cm in height, and the isthmus is approximately 1.25 cm in length. The gland is situated in the front of the neck, behind the thyroid cartilage. Each lobe of the thyroid gland is usually positioned in front of a pair of parathyroid glands. Each of the four parathyroid glands is approximately 6x3x1 mm in size, and weighs between 30 and 35 gms. There can be some variation in the number of parathyroid glands among individuals, with some people having more than 2 pairs of glands.

Endocrine System within the Body

The thymus is an endocrine organ situated behind the sternum (also known as the breastbone), between the two lungs. It is pinkish-gray in color and consists of two lobes. Its endocrine function complements its role in the immune system, being used for the development and maturation of thymus-derived lymphocytes (T-cells). This organ is unusual because of its activity peaks during childhood. After adolescence, it slowly shrinks and gets replaced by fat. At its largest, before the onset of puberty, it can weigh nearly 30 gms.

The adrenals are placed above the kidney and therefore also known as suprarenal glands. They are yellowish in color and surrounded by a capsule of fat. They can be seen just under the diaphragm and are connected to that muscular organ by a layer of connective tissue. The adrenal glands consist of an outer medulla and an inner cortex, having distinct secretions and roles within the body.

The pancreas plays a dual role, being an integral and important part of both the digestive and endocrine systems. The glandular organ located close to the C-shaped bend of the duodenum, and it can be seen behind the stomach. It contains cells with an exocrine function that produce digestive enzymes as well as endocrine cells in the islets of Langerhans that produce insulin and glucagon. The hormones play a role in the metabolism and storage of blood glucose and thus the two different functions of the organ are integrated at a certain level.

The gonads also have important endocrine functions that influence the proper development of reproductive organs, the onset of puberty, and maintenance of fertility. Other organs such as the heart, kidney, and liver also act as secondary endocrine organs, secreting hormones like erythropoietin that can affect red blood cell production.

Endocrine System Structure

Unlike some body systems, the endocrine system is widely distributed within the body. Further, unlike some systems, the parts of the endocrine system can function independently from one another to regulate and coordinate the body. For example, the pineal gland in the brain responds to light received in the eyes, which causes it to release the hormone melatonin. This action can be completely separate from the actions of the reproductive endocrine glands, which are responding to a different set of signals to enable a different outcome.

However, some glands like the thyroid and hypothalamus also control other glands and their functions. These glands can help to coordinate the overall actions of the system and the body as a whole. A release of hormones from these glands can create a cascade of effects from the release of a single hormone. This makes the endocrine system one of the most complexly structured body systems.

Diseases of the Endocrine System

Endocrine system diseases primarily arise from two causes – either a change in the level of hormone secreted by a gland, or a change in the sensitivity of the receptors in various cells of the body. Therefore, the body fails to respond in an appropriate manner to messenger signals. Among the most common endocrine diseases is diabetes, which hampers the metabolism of glucose. This has an enormous impact on the quality of life since adequate glucose is not only important for fueling the body, but it is also important in maintaining glucose at an appropriate level to discourages the growth of microorganisms or cancerous cells.

Imbalances of hormones from the reproductive system are also significant since they can influence fertility, mood, and wellbeing. Another important endocrine gland is the thyroid, with both high and low levels of secretion affecting a person’s capacity to function optimally, even affecting fertility in women. The thyroid also needs a crucial micronutrient, iodine, in order to produce its hormone. Dietary deficiency of this mineral can lead to an enlargement of the thyroid gland as the body tries to compensate for low levels of thyroid hormones.

Diabetes

Diabetes, or diabetes mellitus, refers to a metabolic disease where the blood consistently carries a high concentration of glucose. This is traced back to the lack of effective insulin hormone, produced by the pancreas, or a lack of functioning hormone receptors. Diabetes mellitus could either arise from a low level of insulin production from the pancreas or an insensitivity of insulin receptors among the cells of the body. Occasionally, pregnant women with no previous history of diabetes develop high blood sugar levels. This can threaten the health of the mother and fetus, as well as increase all the risks associated with childbirth.

Insulin is an anabolic hormone that encourages the transport of glucose from the blood into muscle cells or adipose tissue. Here, it can be stored as long chains of glycogen, or be converted into fat. Concurrently it also inhibits the process of glucose synthesis within cells, by interrupting gluconeogenesis, as well as the breakdown of glycogen. A spike in blood sugar levels causes the release of insulin. Its release protects cells from the long-term damage of excess glucose, while also allowing the precious nutrient to be stored and utilized later. Glucagon, another hormone secreted by the pancreas (alpha cells), acts in an antagonistic manner to insulin and is secreted when blood sugar levels drop.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is a condition where the body has an insufficient supply of thyroid hormones – thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Both these hormones contain iodine and are derived from a single amino acid – tyrosine. Iodine deficiency is a common cause for hypothyroidism since the gland is unable to synthesize adequate amounts of hormone. This can arise due to damage to the cells of the thyroid gland through infection or inflammation, or medical interventions for excessive thyroid activity. It can also arise from a deficiency in the pituitary hormone that stimulates the thyroid. Alternatively, it could be due to defects in the receptors for the hormone. Thyroxine is the more common hormone in the blood and has a longer half-life than T3.

Hypogonadism

Hypogonadism refers to a spectrum of disorders where there is an insufficiency of sex hormones. These are usually secreted by the primary gonads (testes and ovaries) and affect the development, maturation, and functioning of sex organs and the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics. It can arise due to a low level of sex hormone production by the gonads itself, or the insensitivity of these organs to cues from the brain for hormone production. The first condition is called primary hypogonadism and the latter is called central hypogonadism.

Depending on the period of onset, hypogonadism can result in different characteristics. Hypogonadism during development can cause ambiguous genitalia. During puberty, it can affect the onset of menstruation, breast development and ovulation in females, delay the growth of the penis and testicles, and affect the development of secondary sexual characteristics. It can also impact self-esteem and confidence. In adulthood, hypogonadism leads to reduced sex drive, infertility, fatigue or even loss in bone and muscle mass.

Quiz

1. Which of these organs secretes glucagon?